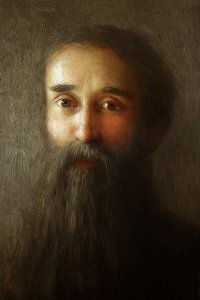

Derek Ball: I didn't live in a thatched cottage, but there were several thatched roofs in our street, in Letterkenny. At that time, it was common to see children in bare feet. Our milk was delivered to our doorstep in cans each morning, from a small dairy farm next door. My parents both played instruments when they were young, but less and less as our family grew up.

When I showed a strong interest in music, my family got a piano. I was about nine or ten years old. I quickly found out how to write music down, and started composing little piano pieces. Archie Potter saw some of this immature work and after I went to Dublin I studied composition with him, and piano with Carmel Turner, as well as doing music in the Inter and Leaving Cert 'of course', at the Royal Irish Academy of Music. Later, Jim Wilson was my composition teacher for a couple of years. Instead of going to the University of music, I did medicine. That held back my musical development a little bit!

My wife is Scottish – we met while working in Jersey, married in Dublin, and moved to Glasgow in the late 1970s, just to work for six months. Then we decided to stay in Scotland. We often visit Ireland, particularly to Donegal and Dublin, where I have lots of family, extended family, and friends all over the place. My music gets played more in Ireland than in Scotland, and I always try to be there when it happens. There's something good about Ireland for composing. I usually spend a month in Donegal in the autumn, just writing. When I go to Dublin for a week, I often come back with half a dozen of new composing projects in my head.

Irish influences

In recent years, poets, especially Irish poets writing in either Irish or English, have become more and more important to me. Part of that is down to my rediscovery of song, which I took a prolonged break from between the early 1970s and about 2005 (when I retired from medicine and immediately wrote a huge opera). In addition to song, now and then, if a poem has a powerful effect on me, I write a piece in response to it.

My most important compositions are my orchestral pieces, particularly my viola concerto (dedicated to the late Charlie Maguire) mainly because, as people tell me, the orchestra is endangered in the modern age as a result of its high cost and its failure to evolve; also, my pieces relating musical rhythm and speech rhythm, like The Mischievous Boy (on a long poem by Maurice Harmon), because they opened up for me a new way of musical thinking; and the opera in Irish Síle an tSléibhe, because of its strong connections, albeit at some distance, to traditional Irish music. I'm often unaware of it while I'm doing it, but quite often I can hear the influence of traditional Irish music in retrospect. Regularly hearing this music must naturally affect the way we think musically.

Composing for the Celtic harp

When I was a child, the small harp was almost unknown. As often happens with emigrants, I gradually came to love this instrument a lot more after leaving Ireland. But the main thing which influenced me was my daughter's decision, at the age of about eight, to take up the Scottish nylon-strung harp equivalent of the Irish harp (not to be confused with the wire string clàrsach or cláirseach of course). I suppose the other big factor must be the revival of the instrument alongside the language and cultural revival movements.

My first properly idiomatic piece for Irish/Scottish harp was probably Ceithre Ráithe na Cláirsí, written in 1995. We came to the Rencontres Internationales de Harpe Celtique de Dinan where we had the memorable experience of hearing the famous Myrdhin live in concert. What struck me was a lecture about the small harp which included the relationship between the construction of the instrument and the position of the sun at midday on the summer and winter solstices. Each section represents one of the four seasons and is dominated by the strings where the shadow of the 'jewel' on the pillar falls on the soundbox at that time of year.

Previously mentioned, Síle an tSléibhe contains electro-acoustic sounds along with live whistles. Some of the recorded sounds are sampled from a real harp and used as follows. I meticulously bent the sound of each note so as to make non-diatonic scales (equally tempered, but with fewer than twelve notes per octave), then used those notes not only for melodic elements but painstakingly put together in swirling glissandi, to represent the unearthly harps of the aos sí, the fairy people.

Songs and Stories of Caílte's Time

My most recent piece for harp is also the biggest: Songs and Stories of Caílte's Time is a large suite of harp pieces with interpolated accompanied songs and readings of prose and poetry, all extracted from a modern Hiberno-English translation of a medieval Irish classic called Acallam na Senórach ("Dialogue of the Ancients"). The process of writing this piece has helped me to feel closer to the deep past of my country and culture: some events may have happened in the 3rd century refracted through the mind of an anonymous cleric in the 12th century. The Acallam (or Agallamh in modern Irish) describes an imagined tour of Ireland with the Fian hero Caílte as tour guide and St Patrick himself as appreciative tourist! What the music aims to do, as much as possible, is to respond to concepts contained in the text, for example: there is a representation of the way Druidic culture superimposes itself on that of the Tuatha Dé Dannan, only to be covered over itself by Christianity.

The poet Maurice Harmon, who recently published a new modern translation of the Acallam (The Dialogue of the Ancients of Ireland), suggested the idea to me. An early, half-hour version of the piece was performed as part of Maurice's 80th birthday celebrations in 2010. The performers were Anne-Marie O'Farrell, Irish harp, and speaker Séamus mac Gabhan. We're hoping to be able to tour the finished version (lasting over an hour) next year.

In Songs and Stories of Caílte's Time, the blades of the harp are set in an irregular tuning which is different in each octave. This tuning is then completely unchanged throughout the whole length of a piece. This is by far my most extensive use of that practice. It gives the piece a unified sound, yet suggests possibilities for interesting combinations. What seems natural to the Irish harp would be completely impossible to play on a concert harp and tricky if you were unwise enough to try it on the piano.

Composing for the Irish harp is neither easy nor difficult. Some pieces just demand to be written, to that extent ease or difficulty are irrelevant. It would be difficult to stop myself, it's easy just to go along with itDerek Ball

The piece chooses its own ideal medium. However, more than with some instruments, harp writing benefits from access to a harp while writing. It's quite easy to imagine something and find, when you try it out, that it doesn't really go well on the harp, or is ridiculously difficult and unrewarding to play. Certainly no-one writing for the harp should rely on the piano as a guide! – the two instruments are very far apart.

At the moment, I'm extending my Caílte's Time piece a little in preparation for an attempted tour next year; planning another attempted tour of voice and brass pieces; finishing a two hour duet song cycle; seeking funding for developing a play-opera hybrid; planning a big piece for three church organs; and putting together a series of voice with electro-acoustic pieces… I should try to keep myself busier!

For more details on Derek Ball and his music, visit the Dublin Contemporary Music Centre’s website.